Review: Pentiment is an outstanding tale of monks, mystery and murder

Obsidian’s monastic mystery is much more than it first appears

- Director

- Josh Sawyer

- Key Credits

- Hannah Kennedy (Art director), Alec Frey (Producer)

In Pentiment, all is not as it seems. The word itself refers to images buried beneath images; remnants of earlier work that can still be seen through the newer paint on top.

In Obsidian’s narrative adventure that takes on a literal relevance – the tale revolves around an illustrator in 1518, constantly tinkering with a would-be masterpiece – but also serves as a handy metaphor for a mystery that soon engulfs the artist’s life. What is a crime story if not the gradual reveal of truths lurking below the surface detail?

Pigeonholing Pentiment as a murder mystery is over-simplifying what the creators have achieved, though. You play as Andreas Maler, a manuscript illustrator in a monastery in Tassing, located in rural Bavaria.

When the grim reaper strikes in the cloisters Maler is pulled in as an impromptu investigator, but this is hardly a medieval Ace Attorney. Much less shouting, for one. Not really the done thing in a house of god.

There is evidence collecting and lead following, sure, but also a ticking clock hanging over proceedings. A lawman is on his way and expects answers on his arrival, meaning the work is rushed and you are doomed to an imperfect investigation.

This isn’t a criticism, but a tempering of expectations. Come to Pentiment expecting black-and-white detective work with a tidy right/wrong answer and you’ll feel hurried and unsatisfied. I’ll admit, this was my initial mindset and it took a few hours to lock into the pace and tone of the story.

Elements click together when you realise that the murder is an invitation to pry into the lives of the monks, their neighbouring nuns and the nearby villagers. While time is limited, you’re free to explore Tassing and the game is explicit about events that move the clock forward – such as attending a sewing circle to gather local gossip, say, or choosing to share a meal with a family.

As you munch through your eighth consecutive ploughman’s lunch you are mentally adding to an ever-growing list of affairs, frauds and grievances that define the community. It’s amazing the bodycount is as low as it is.

“Elements click together when you realise that the murder is an invitation to pry into the lives of the monks, their neighbouring nuns and the nearby villagers.”

What you learn alters the case you’re building. Do you spread yourself thin and seek a basic understanding of all the potential suspects? Perhaps you focus on firming up your case against an obvious git.

This is where Pentiment strays most from a traditional detective game: rather than uncovering the actual perpetrator – a hard truth the game never explicitly reveals – it’s an opportunity to use the investigation to your ends. If you believe a good person killed for the right reason, should you falsely accuse an actively malicious townsperson instead?

It’s here that Obsidian’s studio DNA is most clearly felt: it’s a detective game as moral conundrum, and with a brilliant time-hopping structure in place to help interrogate the fallout of your actions.

Without spoiling plot specifics, Pentiment returns to Tassing several times over the years to both check in with a cast you grow to know and love – I let out a genuine “no way!” when I saw one particularly decrepit old man had survived yet another harsh winter – and see how Maler’s interfering set the community on a better or worse path.

The makers of Fallout New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity being good at choice and consequences may not sound like a surprising headline, but Pentiment is more effective than anything I’ve played from the studio.

By focusing on a relatively small area over a long stretch of time – rather than the immediate outcomes of a thousand decisions across a continent – you build not just an affection for a place and its people, but an active memory of the successes, failures and traumas (some you inflicted) that everyone now lives with.

It allows a subtlety to the characters and writing I was not expecting; an awful lot can go unsaid because we were all there five or ten years ago when The Bad Thing happened. There’s no need for naff expository lore dumps from NPCs who talk like Wikipedia pages.

That such a believable naturalism should emerge from something that looks so beautifully artificial – it’s presented as a living illuminated manuscript, right down to characters having fancier fonts the more educated they are – is a pleasant surprise.

“That such a believable naturalism should emerge from something that looks so beautifully artificial – it’s presented as a living illuminated manuscript, right down to characters having fancier fonts the more educated they are – is a pleasant surprise.”

The team cite Night in the Woods and Oxenfree as mechanical inspirations; this is an interactive story anyone can pick up and play, with cute minigames to draw you into village life. Things like spinning wool or cutting cookies for a Christmas festival – basically WarioWare: Peasant Edition.

The bigger echo is Cing’s cult Nintendo DS adventures Hotel Dusk and Last Window; not just in the use of side activities to draw you into a world, but in its exploration of often low stakes domestic drama in extreme detail and a willingness to slow the pace right down to let you bed into Tassing and its various lives.

That isn’t to say there aren’t moments of explosive drama – when things go wrong in Pentiment they go wrong in a big way – but it’s a tale to be savoured over long winter nights rather than rushed in a weekend.

Pentiment’s leisurely pace is at its riskiest in its opening hours where you’re not just learning Maler’s place in Tassing but wading through stodgy historical scene setting. This is clearly a dutifully researched passion project – it’s the only title I recall having a reference reading list in the credits – but it does wear that intelligence on its sleeve.

Text is peppered with references to historic events and European happenings that are explained in their own glossary on the pause screen and, for the first two hours or so, it all feels a little cold to the touch.

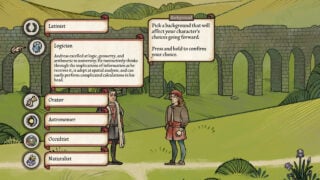

Being asked to define Andreas’ background is a particularly humbling moment. Am I dooming myself to an underpowered build if I select a Flemish upbringing? In hindsight, no, but it’s easy to be put off by this esoteric framing.

In time, this settles. After the first act you’re fully embedded in Tassing and the history you need to understand is the history you’ve experienced. But as first impressions go it didn’t reflect what I came to love about Pentiment.

Here is a story about the challenges of holding onto knowledge in an age of competing dogma, violent overhauls and the delicate impermanence of paper records. Maler is scrabbling through rumour, myth and half-remembered childhood yarns – a very lived-in version of history, which runs counter to the history lessons sketched in the margins.

But this is a minor bugbear, and more of a call to stick with the stodgier early stretch, as Pentiment is worth sticking with. Hour by hour you watch Obsidian adding its brushstrokes, as history lesson becomes murder mystery, murder mystery becomes inquisition power play and the ripples of those actions are unleashed on future stories you’ll experience first hand.

Come the game’s quietly devastating final moments it’s very hard not to look back through those layers and admire Obsidian’s comprehensive portrait of life and death and all the messy business inbetween.

Learn to move at Tassing’s sedate pace and patience will be rewarded as a seemingly simple murder mystery makes way for a rich portrait of village life and the difficult choices that come to define it.

- A deep story builds over the years

- A cast you grow to know and love

- Reactive choices and consequences

- A compelling underlying mystery

- Takes until the second act to click

- Initial history drops feel overbearing