I’ve been working on games for 20 years, and Control is my best work

In structure, gameplay and story, this is everything I’ve wanted to do with a game

Mikael Kasurinen

Mikael Kasurinen is a game director at Remedy Entertainment. Mikael was talking to Andy Robinson.

Control was very much a personal project for me.

I started at Remedy around 2001, when we were making Max Payne 2. I went on the become the lead gameplay designer on Alan Wake and then I decided I wanted to go and work on some different types of games.

I love story-driven games but in my heart I also like games that are more open-ended; RPGs and things like that, where I’m in the driving seat, journeying through a world and it’s up to me to figure things out. So I went to work at Avalanche Studios on the Mad Max game and then later DICE to work on Battlefield 4.

One day I got a phone call from Sam Lake, Remedy’s creative director who I worked with on Alan Wake, and he asked if I’d like to come back as game director on Quantum Break. It felt like the right time so I decided to return to the company. But even then, I was already thinking about what I could do beyond Quantum Break.

I told Sam that I felt Quantum Break was as far as Remedy could go with cinematic games; we had Hollywood actors, an entire TV show, tons of cinematics… it was as cinematic as we’d ever been. I started talking about getting Quantum Break done, which was a cool game, and then after that working on a game with a different approach.

I wanted to look at a different way to do a Remedy game; I wanted it to be more open-ended, more Metroidvania, more RPG. A game that’s more about the world that you go into, instead of being about a singular character.

That was the first time we started putting ideas together for Control. And we started in a different way to how we usually build our games. For example, with Alan Wake we came up with a story about a writer whose stories come true, then we built everything around that; the world, the gameplay… it all revolved around the screenplay.

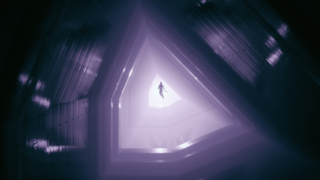

For Control, we decided purposely not to do a screenplay. We decided first to talk about the world: what is this place? A strange, shifting place that corrupts and transforms everything around you. The idea of the Bureau of Control, this organisation that investigates supernatural phenomena and tries to harness it or contain it when it gets dangerous. Also, the feel of the world: it’s realistic, it’s not about werewolves and vampires… it feels gritty and real.

“We would have seen that sort of thing as a danger in the past. At Remedy we became used to the idea that no, we define everything that happens in the game, we define the experience and every single second of that.”

We established that world first and then we started work on everything else. What kind of stories can we tell? Not just one, but multiple stories. Yes, there’s a main character and a core arc for what she needs to do to control the crisis at hand, but as you explore the world you discover optional side-missions that are vast, complex and totally optional.

We would have seen that sort of thing as a danger in the past. At Remedy we became used to the idea that no, we define everything that happens in the game, we define the experience and every single second of that. Here we have a world that’s more complex and the player can choose what they experience.

Once we progressed beyond the initial concept, there were a lot of challenges we had to tackle like, how do we tell a story in this kind of environment, when we can’t define every single moment? It meant, for instance, less cinematics and more NPCs, more dialogue.

Those old passive moments can’t be handled in a dynamic world: we are not in control as much as before, so it was a natural shift on how we handle story telling. A lot of those elements started to come together, and it was clear we’d made the right choice.

As developers, we are not in control anymore. We have created a place that you can come into and it’s up to you what to do. We’ll tell you the setup and then let the player decide how to tackle it.

For example, I didn’t want to have quest HUD markers, which might seems like a little thing but it’s a hugely important decision for the kind of experience players will have. The mission log will tell you that you need to find a certain person or whatever, but it’s then up to you to figure it out. If we had quest markers always telling you where to go next, it creates tunnel vision: that’s suddenly the only thing you’re looking at.

Without the quest markers, you start looking at the environment and figuring out what this place is for yourself. As you do that, you feel more involved and who knows what you might find as you explore? You might find other characters, side-missions, lore, resources to improve your character or you might get lost, which is actually fun in this game. I wanted players to pay more attention to the world: it might not be the most effective way to get through the experience, but that’s not the point, is it? The point is to have an experience.

“I want the game to haunt you a bit: some of the things that you see don’t make sense and it percolates in the back of your head for a while.”

Early on we knew the telekinetic attacks were going to be tough to create. For the player it feels natural and streamlined, but a lot of work went into that. Basically, we revamped our entire engine for this game; we changed the physics engine from Havoc to PhysX, we redid the animation system to more of a gameplay-driven system, and AI was upgraded too.

All of those changes meant that we needed to have a different mindset when we created environments. Usually in games environments are very static and anything that moves requires lots of extra work and is really hard to do. We decided that we wanted the environment to be a weapon that players can use; it should feel fluid, it should feel real and not game-y or fake. It creates a lot of surprising moments, but it meant a different mindset for how we looked at environments.

Almost every single thing that you see in the world is physical, dynamic and you can telekinetically pick it up and use it as a weapon. There are a lot of algorithms going on in the background designed to minimise the sense of management in the experience. When you pick up a chair, it just works. When you target an enemy, there’s a slight assistance happening too. I wanted it to feel simple and natural.

With the story, we decided that we weren’t going to explain anything that didn’t need to be explained. Important information is given to the player and then we leave everything else to the player to figure out, which I think created a more gripping, mysterious experience overall.

“I’ve been working on games for 20 years and this is everything that I ever wanted to do with a game, in structure, gameplay, RPG elements and story.”

I didn’t want to have to tell players the answers to our mysteries. I realised very early on that we needed to be very careful what we said to the press in particular, but that all serves the experience of getting into the game and understanding what’s there. I want the game to haunt you a bit: some of the things that you see don’t make sense and it percolates in the back of your head for a while.

Overall, Control is the best game I’ve ever done. Easily. I’ve been working on games for 20 years and this is everything that I ever wanted to do with a game, in structure, gameplay, RPG elements and story. We learnt a lot of lessons along the way, for sure, but for now it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.