Interview: The real story behind GoldenEye HD, as told by its directors

Co-leads break their silence on the game they say will never release

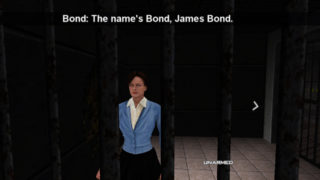

GoldenEye’s HD Xbox remaster has been the stuff of legend in gaming circles. Until, that is, a functioning build of the cancelled project leaked onto the internet earlier this month.

Before the public could fire up an emulator and try it for themselves, all we knew of the N64 remaster were details leaked in a 2008 UK magazine and the occasional tantalising video clip uploaded to YouTube during the past decade.

Unsurprisingly, speculation has been rife around why the project never came to be: Was it cancelled because of Nintendo? Did Bond rights holder Eon get involved? Maybe Robbie Coltrane filed an image rights lawsuit?

As with most internet myths, the truth is slightly less exciting and significantly more complex than the rumour mill would have you believe.

GoldenEye Xbox Live Arcade, as it was codenamed, ultimately failed because of miscommunication between license holders and a young team who rushed ahead to create it, despite a deal for the game having never been signed.

Speaking publicly together for the first time about the project, Goldeneye XBLA’s co-project leads Mark Edmonds and Chris Tilston told VGC that the game was born from a phone call with Nintendo, and ultimately ended when the same company’s executives changed their minds over allowing them to release it.

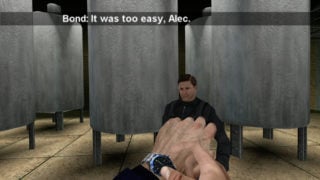

The pair described the remake as “the easiest project” they ever worked on, with their eight-person team completing it in little over six months without scheduling or production. But they also admit that they jumped in early.

In 2007 Rare’s company culture was changing drastically. Whereas projects previously had the endless backing of their founders, which gave them the time and freedom to evolve, the studio’s teams now found themselves in a far more uncertain environment than what they’d enjoyed previously.

Following the completion of Xbox 360 launch titles Perfect Dark Zero and Kameo two years earlier, the teams had been split into small groups assigned with creating prototypes for potential future projects, but none of them would release.

Tilston and Edmonds’ team, who were comprised of former developers of Perfect Dark Zero, had been working on an ambitious MMO project, but according to them, it was cancelled “weeks” after the Stampers left the company.

As fate would have it, at the same time Tilston heard from Rare’s long-time producer Ken Lobb – formerly of Nintendo but now at Microsoft – that Nintendo had presented it with an offer: ‘We want to release GoldenEye on Wii, and in return, you can also release it on Xbox’. Fearing that his team would soon be broken up, Tilston jumped at the chance to hand them a project which – ironically – he felt had a good chance of making it to release.

Speaking to VGC over a video call, the two co-project leads shared the real story behind GoldenEye Xbox Live Arcade and their reaction to the project’s leak this month.

What’s it like seeing the GoldenEye Xbox project finally in the wild after all these years?

ME: It brings back lots of memories of working on it. I think in my mind, the original GoldenEye and the Xbox Live version had sort of merged, so it’s really good to be reminded of the differences in the graphics and framerate.

CT: It’s kind of bittersweet, because it means people get to see the work that was done, but it also masks some of the cockups that went on behind the scenes.

Were you surprised that it leaked?

ME: The thing that I find strangest is, why now? Why leak it after all this time? Someone must have had this for all those years. It just seems strange to me. When I first heard about it, it almost made me think, are Microsoft leaking it on purpose for some reason? (Laughs) I don’t think that would make sense, but it does make you wonder.

So how did the GoldenEye Xbox project come about?

CT: In 2007 [Rare founders] Tim and Chris Stamper had left Rare and without their protective blanket the game we were working on at the time was shuttered. From my perspective, I felt a bit of a responsibility for the guys that followed us. We had a contact at Microsoft who said, ‘there’s this opportunity where Nintendo want to release GoldenEye, and in return you can do whatever you want with GoldenEye on Xbox’. It seemed like a really good opportunity to give the team something to get stuck in to, because we were only a small team of eight.

ME: Oh, did it all come from Nintendo? I can’t remember that far back.

CT: Yep. Nintendo reached out to Microsoft via our contact there [producer Ken Lobb], who we’d done a lot of games with before. Everybody wanted it. For Activision it was free money, for Microsoft they saw it as a way of having a really large hit on Xbox Live Arcade, when there really hadn’t been a million-seller before. We weren’t privy to the details, we just thought Nintendo got to do what they wanted. Potentially they thought we were going to do a straight port on our side.

Can you tell us about the other team members who worked on the Xbox version?

CT: We had a super talented team. Our programmers were Dave Herod and Laurie Cheers, who worked with us on Perfect Dark Zero. Keith Rabbette was a company veteran from Perfect Dark Zero and Star Fox Adventures. Ross Bury we’d also worked with on Perfect Dark. Chris Woods is a super talented background guy who’s gone on to join 343, and Sergey Rahkmanov was a Russian guy who was excellent at characters.

They were super over-qualified for this port. I think it was the only project I’ve worked on where we went home at 5pm every day. It was all super smooth: there were no politics… it was just a lovely team to work with.

We’d just finished Perfect Dark Zero and the Kameo team had finished Kameo, and some bright spark had the idea of splitting up the teams to make prototypes. We made about seven or eight in the end, which from a financial standpoint makes sense by spreading the risk, but from a practical sense none of those teams were equipped to take those games forward. I think every single one of the prototypes were eventually cancelled, which was sad.

The old way Rare would’ve operated is they would’ve pushed the majority of people onto the team and you’d maybe end up with more than you needed to start off with. The [financial] rewards were good, so you knew what you were signing up for if the game was going to be a success. But when new guys started, they wouldn’t really have much choice on which game they’d end up on. So you’d have guys who’d maybe not shipped a game in five years, simply because they’d got assigned to Team X or Team Y.

“Nintendo reached out to Microsoft via our contact there [producer Ken Lobb], who we’d done a lot of games with before. Everybody wanted it. For Activision it was free money, for Microsoft they saw it as a way of having a really large hit on Xbox Live Arcade, when there really hadn’t been a million-seller before.”

Mark, you worked on the original GoldenEye. It must have been exciting to find out you were going to get the chance to revisit the project?

ME: I can’t remember! It seems like it would’ve been exciting! (Laughs) I guess it was like revisiting an old friend from the past. The idea was to really keep the Xbox version true to the original. So it was intended for fans of the first game and to improve it in ways we could, while still staying faithful to that original game.

CT: For me it was more about… a couple of months of downtime at Rare was a long time. You felt like you really needed to pull your finger out and get things moving forward. So GoldenEye at the time felt like a good opportunity to give the guys who followed us a bit of a payoff.

Because I think we were clear with the prototype we were working on before that it was ambitious – it would’ve been the most ambitious game that Rare had ever done by a couple of levels. So they knew what they were signing up for. Some people realised that and didn’t want to join that team, so for me it was more about giving those guys a project they could finally get something out of.

ME: It sort of makes it worse that GoldenEye then never came out! (laughs)

What were your early aspirations for the project when you first started?

CT: Truthfully, I didn’t do much on the design side. We wanted to add online multiplayer and like Mark said, keep it true. I think we added a couple of new multiplayer levels and tied it all into Xbox Live with leaderboards, Achievements and all that stuff.

We wanted to keep it short, to be honest, because the worst thing that anyone could give us as a team was extra time because we probably would’ve added a ton of features that maybe weren’t necessarily needed. So like Mark said, it was about keeping it authentic or as close to the original as possible. Probably the biggest change we made was updating the controls.

ME: I would’ve thought it was networking?

CT: Yeah. I seem to remember we had a version that worked across Xbox Live.

ME: If we were that close to the end, it must have done. On controls, a lot had changed in just ten years. But other than moving to two sticks, I think we tried to keep all of the original code running as it was, so it made it easier for us to convert it.

So the remaster ran on the original code?

ME: Yeah, so we took the original code and then Laurie [Cheers] began converting it chunk by chunk, He got the basic game loop running on the Xbox, then he moved on to drawing the characters and other stuff, changing as little as possible.

I think it was C code on the Nintendo 64 and C++ on Xbox. We were keeping all of the code the same, so when you were walking around the game the collisions were exactly the same on both versions. That basically meant we had to keep the same graphics so that the collisions would be the same and things like that.

It was enjoyable to see it slowly come back to life, with Laurie starting with this small core and slowly adding bits on as they were converted. It was pretty cool.

One of the most impressive features planned for the remaster was the ability to switch between new and old graphics. Was that always intended to go into the final release?

ME: I think that was always planned, once we decided we were going to have new graphics.

CT: It’s like Mark said earlier, that he can’t remember what the Xbox and N64 graphics were like. Back then it was a big difference, but when you look at it now it’s not as huge. It just seemed like a good way of reminding the audience that we’d actually done something!

ME: It does look cool when you switch between the two. I’m not sure how it would’ve worked in multiplayer though.

“We’d send a weekly report to Microsoft to keep them updated and happy, but the issues on our side were always, ‘have we signed the contract?’ And it became a running joke for a while, because things were going so well apart from this one aspect that we didn’t have control of.”

How close was the GoldenEye Xbox project to completion?

CT: We were super close. There were a few graphical issues to finish off and around 90 bugs. I think most of the stuff left was probably just integration. We were able to play multiplayer, the graphics were there… We started it in March [2007] and we were done by Christmas.

ME: Just seeing the videos online of people playing through the whole game, you can see that all the graphics are there.

During development, was there ever any suggestion that the game might not be able to release?

CT: We’d send a weekly report to Microsoft to keep them updated and happy, but the issues on our side were always, ‘have we signed the contract?’ And it became a running joke for a while, because things were going so well apart from this one aspect that we didn’t have control of. We’d sync up every month and ask, ‘have they signed yet? Is this a done deal?’

ME: Now that you mention it, I now remember that. It just went on and on, didn’t it?

CT: Yeah. The longer it went on, the more you started to think, ‘hmmm, there’s something not quite right here’. We started off with the understanding that Nintendo were perfectly happy, and Microsoft were perfectly happy. Rare were I assume happy that we were doing it and they just let us get on with it.

Instead of having eight people doing nothing all day, we were trying to be proactive and get something positive done for the company. It was only towards the very end that we realised that somebody at Nintendo had not asked or got permission of really whoever needed to be asked.

ME: I’m sure at some point that we were all told as a team that everyone had approved it. I can’t remember when that was, but I remember somebody telling us everyone had approved it and it was good to go. Something must have changed after that.

CT: Yeah, I think somebody [at Nintendo] found out about it. That’s the only explanation.

So after a decade of speculation, can you finally give us the definitive answer: why was GoldenEye XBLA cancelled?

CT: From our side, we just heard that one group didn’t want to do it anymore – or was unhappy that the game that they believed originated on their platform was going over to Xbox. I can understand it. If you look at it from a purely mechanical point of view, Nintendo paid for the game originally for their platform – it wouldn’t have existed without them.

But we thought everybody was fine with it, otherwise we wouldn’t have jumped on board. Well, I think we were pretty quick jumping on board – we started it off pretty quick and lots of people were diving in before they could be dispersed to other teams. We started it before it was approved, but a couple of months in we were convinced that everybody was up for it and we had all their backing.

So the issue was with Nintendo rather than Activision or Eon?

CT: That’s my understanding.

There’s been suggestion since that Eon might have disliked some aspects of GoldenEye, such as the violence featured in the game…

ME: I don’t remember us hearing anything from Eon or MGM. I’m not even sure they were involved at all. I don’t even know if they would’ve had to give approval or not for the project.

“We just heard that one group didn’t want to do it anymore – or was unhappy that the game that they believed originated on their platform was going over to Xbox. I can understand it… Nintendo paid for the game originally for their platform”

So was it more of a case that Activision as the holder of the James Bond games rights could simply subcontract its existing agreement?

CT: Yeah, I think so. Again, like Mark said, we didn’t do anything with Eon. The only thing we had to do was… people had left Rare and for anybody’s face to be featured in a game you need their permissions.

ME: Yeah, things like names as well was an issue.

Is that why you killed off Dr. Doak then? Fans don’t seem very happy about that.

ME: (Laughs) Yeah, we had to remove references to people we didn’t have permission for.

CT: The permission for the old assets were already there, but not the new ones.

What about the likenesses of the original movie actors such as Pierce Brosnan? Was that ever an issue?

ME: I don’t know. I can’t remember anything around that! (Laughs) It might go back to the original license that Nintendo bought, because it would have covered these things. Maybe that carried over?

CT: Usually what happens is a producer talks to another producer and shows them the images, then they either approve it or not. There’s one that I imagine was the difficult one, but the only thing we would’ve probably heard about that is, ‘so-and-so actor doesn’t like his image, please change it’. But we assumed that side was being handled by the guys at Microsoft and Activision.

Do you remember when you found out definitively that the project would be cancelled?

As the project went on, the meetings about the contract would get more and more fractious. There’s only so many ways you can ask the same question. So it wasn’t necessarily a surprise. I didn’t feel like we had the backing of the Rare management then to actually do it.

A day or two after GoldenEye was canned, they literally split the team up and scattered us to the winds. I genuinely believe that was their plan once they canned our earlier prototype, but we kind of stole a march on them by starting GoldenEye in the first place.

Have you been back in touch with the team since the game leaked?

CT: I’ve chatted to Ross [Bury], but I haven’t spoken to any of the other guys. Keith is still around, obviously I work with Mark now again, Dave [Herod] is at Rocksteady… I think there are perhaps different types of developers who enjoy the social aspect and go down the pub and all that kind of shit, and then there are antisocial people like me…

ME: And me!

CT: … who go in and do a job, do our best, have a fun time and go home.

Do you think your GoldenEye remaster will ever release?

CT: No. It’s definitely not going to happen.

ME: I don’t think it will, no.

“Ken [Lobb] was trying to find the original source for KI. I was going through all the old tapes and they were just corrupt… Our backup strategy was kind of laughable!”

Why did Nintendo need Rare’s permission to re-release GoldenEye if they own it?

ME: Anything to do with the original game will be owned by them, but then there’s whoever the other [license] parties are who are around at the time as well.

CT: I imagine that there was a big contract when Microsoft bought Rare, with some agreement between the two on who owns what and how that would work. Maybe the GoldenEye stuff ended up on Nintendo’s plate. We were always under the impression that Activision could have done something with it if they decided to – which probably wouldn’t have made Nintendo very happy.

ME: Nintendo bought the license for the original game and then basically paid Rare to make the game for them. It wasn’t published or owned by Rare in any way.

Do you think as an industry games should do more about preservation?

ME: It’s interesting. It’s like first drafts of books that get preserved. It’s tricky with digital things just because the hardware decays and it’s easy to lose the code so things never run again. All the emulation stuff is the best way for backing things up, so it runs forever.

CT: When Microsoft were trying to start off the Killer Instinct reboot, which was during the last few months I was there, Ken [Lobb] was trying to find the original source for KI. I was going through all the old tapes and they were just… corrupt. We’d stored the stuff on these DAT tapes and before that it was floppy disks, or we’d copied everything to the one big server which was always going down. It was quite amateurish considering that the games would generate a huge amount of money.

Our backup strategy was kind of laughable! So, Mark’s right: emulation is probably the best way of preserving content because the original companies don’t have proper backups. It’s a shame.

Finally, how do you look back on the GoldenEye project?

CT: It was the easiest game I’ve ever worked on. It was almost trivial, because of the quality of the people who were on it. We’d just come off two years of Perfect Dark Zero, which was a year of crunch on hardware that was in pieces. We were 30 people doing a single-player game with online multiplayer and co-op, and even though 75% of the team were new they levelled up really quick.

So when you took some of those guys to work on something like GoldenEye, it was just super easy. We had no real scheduling or production of any kind, because they were just blasting through it so quickly.

It felt like it was a refuge for a while because the founders had left and the company had to discover a new identity. This was a refuge where it felt like you could be effective and still contribute as a small group, without any kind of politics getting in the way. But it wasn’t to be.